קהלת לא תורגמה לפי שלא נכללה מעולם בסדרי הקריאה של הציבור הרחב. למדנים שנדרשו לה יכלו להבין בעצמם פירושים שלה שנכתבו עברית, ולא נזקקו לשרח בערביתQohelet was not translated because it was never included in the readings for the general public. Scholars who studied it could understand its meaning even it if was written in Hebrew and they did not need a translation into Arabic.

- in Marrakech at the beginning of the 20th century on at least two occasions;

- in Sefrou in 1920's or 30's;

- and from a village near Tefilalt some time between 1924 and 1926, created by Moshe Bar-Asher's late father and recorded by professor Bar-Asher in 1983-84, the subject of the paper.

I'm more than happy to add one more to the list, earlier than any of the above and not a manuscript, but rather a printed version dated 5657 / 1896-1897 from the famous press of Solomon Belforte & Co. in Livorno. This one is not a part of my humble collection of late Judeo-Arabic prints, but it can be found in the British Library under the shelfmark 1906.a.42. The booklet contains:

- Song of Songs with its targum and Judeo-Arabic šarḥ of the latter which is quite similar, but not entirely identical to the one in my collection (Livorno 5615 / 1854-55, henceforth ŠM1). The first part also contains commentary on the targum explaining "difficult words and concepts in the Targum" (המלות הקשות והענין שבתרגום);

- prayers for Pesakh (תפלת המחה של פסח);

- and finally, Qohelet with šarḥ.

The title page as well as the introduction on the following page identify the author as Chaim Ha-Kohen The Younger (הצעיר חיים הכהן) and indicate that the work was compiled in Tripoli, Libya (טראבלס המערב). Who the author actually was is still unclear to me. With the reference to Tripoli, the first name that springs to mind is that of Mordechai Ha-Kohen (1856-1929), the author of The Book of Mordechai, a study of the history and customs of the Jewish population of Libya. The other possible candidate is Joseph Chaim Ha-Kohen (1851-1921) who, so his Wiki page tells me, was born in Morocco, moved to Jerusalem at an early age, but then often returned to Maghrib. However, a quick search among the seforim would seem to indicate that either of the two used their full name and neither is identified with one of at least three seforim signed by הצעיר חיים הכהן.

The identity of the author remains a mystery for now, but one detail deserves mentioning: this is the first šarḥ from Libya I am aware of. Whether its language reflects the Libyan dialect still remains to be seen, but I offer here some preliminary remarks, old-school style, based on the first two chapters which you can find here.

(Abbreviations: QL - the British Library Livorno print; QM - Bar-Asher 2010)

Writing:

- The non-assimilated definite article is transcribed without the aleph: לִכְּלָאמָאת "deeds (lit. words)" (1:8), לְכַּל "everything" (1:14). One notable exception is אַלְכַּל in 1:2.

- The assimilation of the definite article is indicated throughout, sometimes also by means of a dagesh (אַגָֹּאהַל in 2:15,16; אַצְּלָאם in 2:13; אַרִּיח in 1:6), but usually without it: אַסִמְס "the sun" (throughout); אַצְנָאיַע "works" (2:17).

- The loss of [h] found in many dialects of North Africa (and in Malta), which results in a number of hypercorrections: הָאנָא "I", הָאש "what" (throughout).

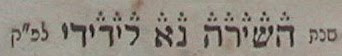

Side note: The coolest such hypercorrection resulting from the loss of [h] has got to be the date on ŠM1. As with many Jewish books (but also everyday items) all over the world, the year is given as passage from the Tanakh with some of the letters highlighted, either through size or in some other way. Add up their numerical values (hint: final forms count as regular ones) and you get the short form year (לפ''ק = לפרט קטן), i.e. without the thousands. This is what it looks like on the title page of ŠM1:

This time the letters to be counted are highlighted using a little crown of dots above them, so השירה נא ליד left to right ads up to 4+10+30+1+50+5+200+10+300+5 = 615, which is the year 5615, i.e. 1854-55 CE. Except if you were to look for these three words in any copy of Tanakh, you wouldn't find them. The actual verse is אָשִׁירָה נָּא לִידִידִי ("Let me sing for my beloved"), from Isaiah 5:1. The author, compiler or printer knew that where they came from, ה was not pronounced and thought - or had been taught - it applied to the text of Tanakh as well. A wonderful example, indeed, but can we rely on the date being correct?

- Assimilation and dissimilation of [s] [z] and [ʃ] [ʒ] (sifflant / chuintant alternation [1]), so typical for Maghribi Judeo-Arabic writing: אַסִמְס "the sun" throughout, לִיס "is not" (1:11 and beyond), but לִיש in the first 8 verses, צַזַר "trees" (2:5, see below), וְיִזְרֶק "and rises" (1:5, see modern Maghribi Arabic šṛəq).

- Much more detailed analysis will be required to fully understand the system (if any) behind the transcription of the vowels using niqqudot. It would appear, however, that both patah and schva stand for [ə] (כְּבַרְתְ וְזַדְתְ "grew and added" 1:16), while qamats stands for [a]. To underscore the point, qamats is usually followed by aleph: מָאשִׁי "goes" (1:6), וַלְנסָאן "human" (2:21). There are exceptions to this, such as צָלְטָאן "the king" (1:1, 2:12) or עָלְמָא "wisdom" (1:16-17). Whether there's a method to this and just what it means (as you will note, in both cases qamats follows an pharyngealized consonant) will remain to be seen.

Phonology:

- Typical Neo-Arabic tafḵīm (pharyngealization): צָלְטָאן "king" (1:1).

- A particularly neat example of both sifflant / chuintant transformation and AND tafḵīm can be found in 2:5:

צְנַאעְת לִי ג'נָאנָת וסְוָאנִי . וַגְרַסְתְ פִיהוֹם צַזַר גְ'מִיע תְמָאר

The highlighted word is a translation of hebrew עֵץ = "tree" and traces back to Arabic شجر. Except in Maghribi Judeo-Arabic, it underwent double chuintant > sifflant transformation to first סז'ר (thus for example in ŠM1 1:16 כַסַזְ'רָא) and then to סזר. Subsequently, the whole word was pharyngealized to something along the lines of ṣəẓəṛ. The translator, however, only had צ at their disposal to indicate pharyngealization, hence צַזַר.

Syntax:

- Much more literal than QM, QL often employs participles where the Hebrew original does, even if fluent native Arabic wouldn't. Thus for example in 1:5, Hebrew סֹובֵב סֹבֵב "turns and turns" is translated as דָאיֶיר דָאיֶיר, whereas QM has more idiomatic יצייר תצוויר, i.e. imperfect followed by the verbal noun, a construction which indicates intensity.

- QL shows preference for the preposition לְ to translate the Hebrew אֶל, whereas QM prefers אילא.

- Like QM, QL uses לִיס for both "is not" and the negative particle.

Word choice:

In most word choices, QL is much more conservative (i.e. less dialectal) than QM. Thus for example:

- QL adopts the Hebrew הֲבֵל (as הְבֵיל), whereas QM uses the Arabic חתוף (with some exceptions).

- QL uses אַלִנְסָאן for "human", while QM uses the typical Maghribi בנאדם.

- QL has יְרוּשָלָיִם for "Jerusalem", while QM uses מדינת אסלאם.

In one instance, it's QM that is extremely literal: in 1:6, QM uses the Hebrew דארום and צאפון for "south" and "north", respectively. Interestingly, QL has here קַבְלִי and בַחְרִי, both terms I would describe as very Egyptian.

- For the relative pronoun, QL uses אַלְדִי with some exceptions, like אֵלִּי in 2:9. QM, predictably, uses the typically Moroccan דדי.

- QL uses אַלְכַּל "everything" substantively, but - like QM - גְ'מִיע as a determiner.

- QM occasionally uses the Neo-Arabic רא for "to see" (e.g. 2:12) while QL sticks with the Classical נְצַֹר throughout.

- QL translates the Hebrew כִּי "because" as לָאייַן.

The rest is forthcoming in the form of a paper, hopefully soon. Ah well, at least I don't have to go far for my new year's resolutions. Boldog új évet, everybody!

References:

[1] Sumikazu Yoda, "'Sifflant' and 'chuintant' in the Arabic dialect of the Jews of Gabes (south Tunisia)", Zeitschrift für Arabische Linguistik 46 (2006): 7-25